The Big Read: Jemaah Islamiyah emerges from the shadows, playing the long game

December 13, 2021

December 13, 2021

Abu Rusdan (left), the Jemaah Islamiyah’s public face, and Abu Bakar Bashir who is the organisation’s spiritual leader. (File photos: AFP)

Abu Rusdan (left), the Jemaah Islamiyah’s public face, and Abu Bakar Bashir who is the organisation’s spiritual leader. (File photos: AFP)

- Following a crackdown by regional security forces, the Jemaah Islamiyah terrorist organisation has switched tack to play a patient, long game.

- Recent arrests in Indonesia suggest that a JI insider had founded a political party, which would be a first for the terror group.

- The creation of a hybrid militant-political force, like the Hezbollah in Lebanon, could be one of JI’s goals, said experts.

- Such a move indicate that JI may be sensing that the ground in Indonesia is turning to its favour.

- Despite attempts to rebrand itself, JI has not truly renounced the use of violence and the Singapore authorities are watching it closely.

SINGAPORE: The Hezbollah, a militant group in Lebanon known for its bloody history of sectarian violence and branded as a terrorist organisation by many countries, shocked the world when it became part of the winning coalition during the Middle Eastern country’s parliamentary elections in 2018.

Presently, the hybrid political-militant group holds considerable sway among Lebanese state institutions, where it enjoys legitimacy without accountability for its actions, concluded a report from London-based think tank Chatham House in June.

About 9,000km away in Indonesia, experts fear that another shadowy organisation with a violent past is watching these events and taking some cues.

Despite crackdowns by security agencies, arrests of several key leaders, and a global war on terror that also saw the emergence of rival groups antithetical to its cause, the scourge of the Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) organisation that terrorised Southeast Asia in the early 2000s still persists today.

Many Singaporeans would be familiar with JI — last week marked the 20th anniversary of the Dec 8, 2001 crackdown against the terrorist group in Singapore, which involved the arrests of dozens of its members and exposed the true extent of the nefarious group’s activities in the region. It subsequently emerged that JI drew up plans to attack nearly 80 targets in Singapore.

Terrorism experts point to how security actions have decimated JI in the region, restricting its clandestine activities to its base in Indonesia, where it had originated.

But there are increasing signs that JI, whose members are estimated to number between 6,000 and 10,000 today, is learning from militant groups such as Hezbollah and the Hamas in Palestine by morphing into a similarly “hybrid” variant of Islamist extremism that will be hard to eradicate.

In recent weeks, intelligence and security-related news emanating from Indonesia have set alarm bells ringing for global security experts. The information reveals how JI could be entrenching itself in legitimate businesses and charities, and even dabbling in local politics.

On Nov 16, Indonesian counter-terrorism police force Detachment 88 arrested three individuals suspected to be JI members, including Farid Ahmad Okbah, who founded the Indonesia’s People Dakwah Party (PDRI) earlier this year.

Farid is believed to be a member of JI’s governing council and his party is a new conduit used by JI, said the Indonesian police which is investigating the links. The PDRI has challenged these assertions.

Police escort a senior JI leader at Jakarta airport on Dec 16, 2020, who was on the run for his alleged role in the 2002 Bali bombings. (Photo: AFP)

Police escort a senior JI leader at Jakarta airport on Dec 16, 2020, who was on the run for his alleged role in the 2002 Bali bombings. (Photo: AFP)

Also arrested for JI links was Ahmad Zain An-Najah, who was a member of the fatwa commission of the Indonesia Ulema Council, which is the country’s top Islamic clerical body and a government-funded organisation.

If the allegations against PDRI are confirmed, this marks the first time that JI has tried to formally participate in the political process in Indonesia by forming a political party, even though its ideology rejects democracy.

Asked about these developments, Singapore’s Internal Security Department (ISD) said that despite the efforts of anti-terror agencies over the years, JI remains resilient and adaptable, even as it beats a tactical retreat.

ISD said JI now appears to be shifting its strategy away from violent attacks and towards the “political infiltration” of political parties, charities and other open-front organisations.

Such efforts are likely to be geared towards “garnering resources and cultivating ground support” for its eventual goal of establishing an Islamic state.

“In ISD’s assessment, JI is playing the ‘long game’ and has not forsaken its militant ideology and ambitions of establishing a Daulah Islamiyah (Islamic state) in Southeast Asia through armed jihad.

“It has also not renounced the use of violence,” said its spokesperson.

The alleged attempts to seek political legitimacy is nevertheless a concerning sign that the “ground” that JI seeks is shifting in its favour, said Mr Mohd Adhe Bhakti, executive director of Centre for Radicalism and Deradicalisation Studies based in Indonesia.

Mr Adhe, pointing to trends towards religiosity in his own country, said: “At this time, there is a feeling of a wave of Islamisation in Indonesia … (whereby) Muslims want to feel closer to religion.

“I think these values of wanting to be more religious have become a catalyst and have been greatly used by groups, including the JI.”

Amid the rise of religious conservatism in Indonesia, the New York Times noted in 2019 a rise in faith politics as Indonesia engages in a “national spiritual reckoning”, adding that puritanical Salafist interpretations of Islam from the Arabic world are attracting followers there.

Associate Professor Kumar Ramakrishna, who heads the International Centre for Political Violence and Terrorism Research at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) said these developments in Indonesia, which has the largest Muslim population in the world, are important to watch.

But it remains to be seen if Islamist political parties can gain a firmer hold at the ballot box, since they have traditionally not fared well in national polls, he said.

In any case, with investigations still ongoing, the opening of a political front for JI poses interesting questions about the future of the banned organisation, said the terrorism expert.

For one, it would be no surprise if JI is picking up pointers from groups such as Lebanon’s Hezbollah or Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, whose candidate Mohammed Morsi won the presidential election in 2012 though he was ousted by the military a year later.

“We are approaching an inflection point as far as the JI is concerned,” said Assoc Prof Ramakrishna.

REGIONAL CRACKDOWN

JI was borne as a splinter cell from a post-colonial separatist movement, the Darul Islam, that sought to establish an Islamic state in Indonesia through violent insurgency, thus rejecting the country’s secular “Pancasila” philosophy set out by its first president, Sukarno, that had brought the diverse indigenous groups of the archipelago together.

When Darul Islam’s leader was captured in 1962, it effectively fragmented the group, and two of its members, Abu Bakar Bashir and Abdullah Sungkar, would later found JI in 1993. Both of them had links with the Al-Qaeda terrorist organisation in Afghanistan, having travelled there in the 1980s.

Abu Bakar, 83, who remains JI’s spiritual leader, was released from prison in January this year after serving 11 years out of a 15-year sentence for funding a militant training camp. His 55 month remission was due to good behaviour and his ailing health.

“By the time JI was formed in 1993, it already had a global jihad emphasis as compared to Darul Islam’s Indonesia-first focus,” said Assoc Prof Ramakrishna.

But with Singapore sounding the alarm on JI in 2001, and following the Bali bombings in October 2002 (Indonesia’s worst terrorist attack which killed more than 200 people), the resulting crackdown against the militant group in Indonesia and other countries disrupted its hierarchical structure, he added.

The group essentially went into a period of relative decline after that and went back to its roots of focusing on Indonesia first, said the terrorism expert.

Over the years since 2002, experts said around 900 JI members have been nabbed. Mr Adhe believes at least seven “emirs” — JI’s top leaders — have been caught as well.

JI, however, remained dangerous and violent in this period of crackdown. Arrests of top leaders could lead to reprisal attacks by other members, and there had been cases of several JI attacks when the organisation lost its leaders to the crackdown, Mr Adhe added.

“So as an organisation, they are very obedient and disciplined, but when they lose a figure of leadership … they become vulnerable and wild,” he said.

THE SEEDS OF NEO-JI

In late 2009, JI leader Para Wijayanto came to prominence within the organisation, and was named as its emir after the arrest of his predecessor Abu Husna in Malaysia.

For a decade until 2019, Para Wijayanto sought to resurrect JI from its diminished state by refocusing its objective within Indonesia first, pausing the violence that the militant group had become known for, given that this had kept JI high on the security radar of anti-terror forces.

Indonesian police personnel show photographs of JI leader Para Wijayanto and various seized items at a press conference in Jakarta after his arrest in 2019. (Photo: AFP)

Indonesian police personnel show photographs of JI leader Para Wijayanto and various seized items at a press conference in Jakarta after his arrest in 2019. (Photo: AFP)

The evolving strategy of JI at the time led some observers to label the group as the “Neo-JI”.

“JI under Para Wijayanto focused on religious outreach and less on jihad, because the lesson from the JI perspective was that global jihad and violent activities led to a reaction that decimated them,” said Assoc Prof Ramakrishna. “They wanted a long period of gestation.”

Para Wijayanto planted the seeds for rebuilding and regrouping the organisation, into one that would bide its time by developing a strong political base in the community before engaging in jihad again.

“That is the sort of ‘strategic patience’ that Para Wijayanto created — some would call it a ‘jihad-later’ approach,” said Assoc Prof Ramakrishna.

Singapore’s ISD said the regional JI network had remained “quietly active” in Indonesia, expanding its support base through outreach and recruitment activities as well as rebuilding its military capabilities.

“Security forces’ preoccupation with the IS threat in recent years has also given the JI space to regroup,” said the ISD, referring to the terror group Islamic State of Iraq and Syria.

Islamic State’s ideology to create a global caliphate centred in Iraq and Syria, through military conquest of territory, was in conflict with the aims of JI and its affiliates Al-Qaeda and the Taliban in Afghanistan, which among other things, desired to establish an Islamic state based on Syariah law in their respective countries.

In Indonesia, Islamic State-aligned groups, such as Jamaah Ansharut Daulah and East Indonesian Mujahideen, distracted the authorities from the JI threat from mid-2014. Both had carried out bloody attacks such as bombings, including of a Sulawesi church this year, while JI ceased all violent actions.

Associate Professor Andrew Tan, from the Department of Security Studies and Criminology at Macquarie University in Australia, said the sudden and messy United States withdrawal from Afghanistan in August — which paved the way for the return of the Taliban, another Islamist fundamentalist group — was, in fact, a shot in the arm for JI and its supporters.

“The re-emergence of the Taliban has been a huge morale booster to militants around the world. It appears to prove to them that if you are persistent, even in the face of great odds, you can ultimately achieve victory.

“It is too early to say how this event would change the JI’s stance and tactics but it would certainly hearten them,” he said.

BECOMING MAINSTREAM

While JI shifted its rebuilding efforts towards proselytising its cause via above-ground entities such as businesses and charitable foundations, one notable shift during Para Wijayanto’s reign was also to participate in Indonesian politics.

This was a departure from JI’s past stance towards participation in democracy. To the group, democratic elections are a man-made system and anathema to Islam.

In a paper published in June on JI’s hierarchy, RSIS associate research fellow V Arianti described Para Wijayanto’s new approach as a strategy that “emphasises the methodical acquisition and consolidation of influence over territory and to build support”.

Besides an armed struggle, the strategy would emphasise political consolidation by winning over the hearts and minds of Indonesian Muslims, through the group’s existing sermons and religious study sessions, JI-aligned Islamic boarding schools, as well as by courting community leaders over to the JI cause.

In 2016, JI would also involve itself in political mass protests, including the “212 movement” rallies against then Jakarta governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, also known as Ahok, the researcher noted.

Basuki had been accused of blasphemy against Islam in a speech in 2016 and lost the gubernatorial election the next year, and was also sentenced to two years’ jail.

Reports at the time said that JI members had joined the rallies and Para Wijayanto had encouraged its members to vote in elections.

Since the incident, Mr Adhe said there has been a growing wave of conservative Islam among people in Indonesia, with some perceiving the current government of Joko Widodo as anti-Islam.

“This Islamisation wave cannot be separated from the impact of the Jakarta gubernatorial election in 2017 … The negative sentiment which then led to the massive demonstration did not stop when the election ended,” said Mr Adhe.

Assoc Prof Ramakrishna agreed, adding that the Ahok incident likely signalled to JI that people’s views may be shifting in its favour, and may be more open to the group’s more extreme ideas.

In that context, the establishment of a political party that is actually JI in disguise is the natural next step for the terrorist group.

“This is something worth watching. If you asked me 20 years ago, I would never have expected JI to enter into politics,” he said.

He pointed out that whenever Islamic extremist groups go into politics and succeeds in gaining mainstream political legitimacy, one of two things could happen: It could end up pushing the whole political system towards the extreme but on the other hand, it could also force the group to recognise political realities on the ground and moderate its stance further.

In the case of Hezbollah in Lebanon, its victory in the polls did not mean a formal takeover of the state functions by the group, as it was faced with the realities of delivering citizens’ needs when it had little ability to do so.

Since the Beirut port explosion last year, many Lebanese citizens have pointed the finger at Hezbollah for causing the country’s long-running problems, attributing the mismanagement and corruption of the Lebanese state to the group.

Assoc Prof Ramakrishna said: “When (extremist groups) engage in politics, they realise that life is very complicated. There’s no black and white, it’s actually very grey, and they now need to actually work with the people.”

However, some experts believe that JI’s political debut may be a result of a lack of options caused by the massive clampdown against the group, rather than a deliberate change in tack by JI leaders.

Assoc Prof Tan from Macquarie said of the founding of PDRI by a suspected JI insider: “It is probably a necessary tactical move given the loss of operational capabilities as a result of counter-terrorism operations, and consistent surveillance by Indonesian counter-terrorism police.”

Mr Raffaelo Pantucci, a terrorism analyst at Britain’s Royal United Services Institute and a senior fellow at RSIS, noted that whether JI’s recent moves are a result of strategic patience or effective deterrence by the authorities is still a matter of academic debate.

Indonesia’s elite anti-terror squad investigates a suicide bombing attack near a busy Jakarta bus station that killed three policemen. (File photo: AFP/Fernando)

Indonesia’s elite anti-terror squad investigates a suicide bombing attack near a busy Jakarta bus station that killed three policemen. (File photo: AFP/Fernando)

It also remains to be seen whether the PDRI is indeed a JI front, or is only characterised as such because it takes an Islamist stance that differs from the current government, he said.

“Ideologically, if you are a secularist, you could look at those advancing an Islamist narrative and say, well, these guys are all kind of the same group. So, I would question a little bit about whether that’s really what’s happening here,” he added.

A PROBLEM FOR SINGAPORE

In any case, the resurgence of the regional JI network is a matter of grave concern for Singapore, given the group’s history of targeting the country and its links with the United States.

The ISD spokesperson said JI’s comeback “will directly raise the threat of an attack against Singapore and our interests”.

“Notably, Singapore continues to be seen as a prized target by the JI. Singapore and our interests have resurfaced in JI-linked attack plans over the past decade or so,” said the ISD.

For example, in 2010, the Indonesian authorities discovered a map of Singapore’s MRT network – with Orchard MRT station circled – and a street map of Orchard Road, in the possession of a JI-linked terror suspect who was involved in a JI-led militant training camp in Aceh, Indonesia.

Separately, in 2011, the Indonesian authorities also uncovered a plot by a JI-affiliated militant to attack Singaporeans leaving the Singapore embassy in Jakarta.

Although JI’s softer tactics in recent years may have taken some heat off the authorities, the reality is that counter-terror forces in the region have not taken their eyes off the JI completely, even if other Islamist extremist groups with more violent tendencies take priority.

The ISD’s spokesperson added: “Given the serious long-term security threat that JI poses to Singapore, ISD continues to monitor the regional JI network closely, and cooperates with our foreign counterparts through regular intelligence exchanges to counter the JI threat.”

Para Wijayanto was arrested in 2019 by the Indonesian police, which have continued to nab JI members who are involved in other non-military fronts, such as financing and religious outreach.

Despite JI’s tactics to present a gentler face, experts said the militant group has not truly deviated from its doctrine of carrying out violence against secular governments and citizens, as well as against Western interests in the region.

Mr Adhe noted that although Para Wijayanto’s Neo-JI appeared to have abolished its military wing, the “askari”, from its formal structure, the group still maintains its ability to carry out violence by sending personnel to conflict zones to continue their training.

From 2013 to early 2018, dozens of JI members who served in this wing had been successfully dispatched to train in Syria with its affiliate Al-Nusra Front, an ally of Al-Qaeda, he said.

“The violence that they still maintain is always justified as an obligation by the religion. In policy, they seem to disengage from violence, but culturally they still make preparations … in case Muslims are attacked by enemies,” said Mr Adhe.

Mr Pantucci said that as long as the authorities continue to maintain the pressure on JI, as is the case today, the group will continue to lose its relevance.

“What is concerning is that the JI is an organisation that has not gone away, but at the same time it does seem to be substantially degraded because of effective deterrence,” he said.

“The group has not launched an attack in a very long time now, and instead what we see today are a series of arrests of important people in the JI in escalating numbers, and I’d argue that the JI is a shadow of itself.”

Assoc Prof Tan agreed that the Indonesian authorities are not taking any chances, arresting Abu Rusdan, who is JI’s public face, in September.

He said: “Indonesia is demonstrating that it is important to sustain counter-terrorism operations and surveillance to proactively deal with the continued militant threat — something we can all learn from.”

As to how the ISD can guard Singapore against JI’s political moves to legitimise itself or its attempts to win over hearts and minds in the region, the department said the country has a “strong zero-tolerance approach towards any form of extremist or divisive ideologies”, especially if they advocate the use of violence.

“We have drawn a clear separation between religion and politics, with safeguards instituted to preserve our racial and religious harmony,” said the ISD spokesperson.

“These principles remain relevant and pertinent even as the threat landscape evolves. The (Singapore) Government will not hesitate to use the Internal Security Act or other relevant laws against any groups or individuals who pose a threat to the security and stability of Singapore.”

KEEPING WATCH

At present, there is no indication that JI’s activities in Indonesia have spilled into Singapore. Indonesian JI members are not rekindling old ties with their former Singapore associates, nor are there any credible and specific intelligence of any JI-linked plots that target the city state and its interests, the ISD said last week in its report commemorating the 20th anniversary of the JI arrests.

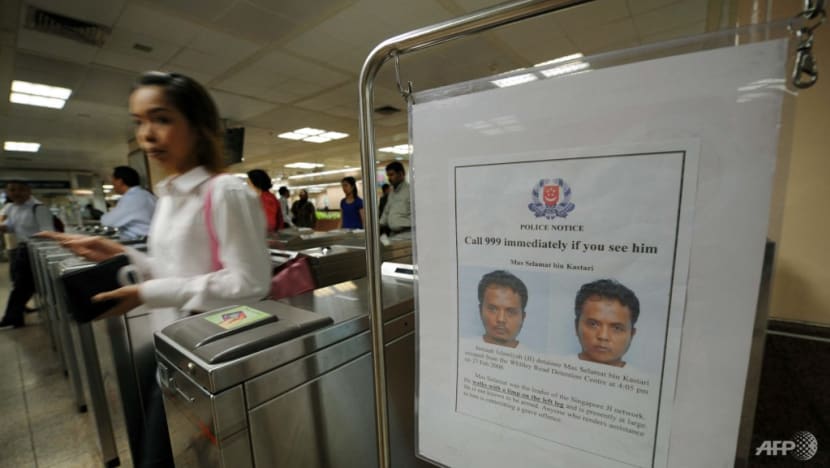

A commuter walks past a poster of JI leader Mas Selamat Kastari at an MRT station in Singapore in 2008. (Photo: AFP/Roslan Rahman)

A commuter walks past a poster of JI leader Mas Selamat Kastari at an MRT station in Singapore in 2008. (Photo: AFP/Roslan Rahman)

In the meantime, the community also plays an important role in keeping Singapore safe and secure, the department said, urging vigilance.

“Besides making a conscious effort to preserve social cohesion, Singaporeans must also remain vigilant. Concrete steps such as flagging out suspicious persons and activities, and extremist online content to the authorities can help to prevent extremism from taking root in Singapore,” it said.

The ISD called on Singaporeans to look out for these signs of radicalisation among people:

- The display of insignia or symbols in support of extremist and terrorist groups

- Frequently surfing radical websites

- Posting and sharing extremist views on social media platforms like expressing support and admiration for terrorists or terrorist groups, as well as the use of violence

- Sharing their extremist views with friends and relatives

- Making remarks that promote ill-will or hatred towards people of other races or religions

- Expressing intent to participate in acts of violence overseas or in Singapore

- Inciting others to participate in acts of violence

Assoc Prof Ramakrishna said that youths are particularly vulnerable to radicalisation. In an age where they are looking for certainty of right versus wrong or good versus evil, they turn to the Internet for answers, he said.

It is thus pivotal that Singaporeans are more aware of these warning signs, and to alert the authorities if they see signs of radicalisation.

Other experts added that people should keep abreast of general current affairs and the evolution of the terrorism landscape, because events happening elsewhere in the world — such as the US’ withdrawal from Afghanistan — have an impact on security here.

After all, the threat of JI had been unknown to Singapore until the 9/11 attacks in the US 20 years ago, which Al-Qaeda had claimed responsibility for.

It was only when a member of the public tipped off the authorities to an individual who claimed to know Al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden that the lid was blown off the JI’s clandestine activities back then.

The difference today is that with JI operating under a changed strategy, experts worry that people may not know what to look out for because the line between moderation and extremism is starting to blur.

New generations of Singaporeans also lack the historical context of Al-Qaeda and its offshoots, including JI, even though their violent plots remain as the country’s closest brush with transnational Islamist terrorism in the past two decades.

Assoc Prof Ramakrishna said: “It is important to be aware of the trends, and I consider this to be part of good citizenry in this day and age. As the saying goes, those who cannot remember the past will be condemned to repeat it.”